Announcing The World Council For Health's policy & briefing document regarding The World Health Organization's dangerous power grabs & threats to human rights & health.

The World Health Organization remains one of the greatest threats to health, survival, and human rights for all of us, and for generations to come. The WHO is the conduit of control used by global predators including the WEF and Bill Gates to abuse and violate the world’s population. Here is an important new tool to help us advance the fight for our survival, health and freedom.

Policy Brief

REJECTING MONOPOLY POWER OVER PUBLIC HEALTH

On the proposed IHR (2005) amendments and WHO pandemic treaty

April 2023

Contents

I. Introduction

II. International Health Regulations Amendments

- Mandatory measures and state sovereignty

- Surveillance: (digital) health certificates and locator forms

- Countering dissent globally

- Cartel rights and regulation

- Unsolicited offers and obligation to cooperate

- Sharing of pathogen samples and genetic sequence data

- Discarding human rights

III. Pandemic Treaty/Accord (WHO CA+)

- Recognizing the authority of the WHO and global health governance

- Tackling dissenting views globally and identification of profiles

- WHO Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network

- Standardization of regulation and acceleration of approval

- Support for gain-of-function research

- Sharing of pathogen samples and genetic sequence data

- One Health and pandemic/epidemic root cause analysis

IV. Rejecting Monopoly Power over Global Health

- The threat posed by monopolies

- Who runs the WHO – structural reality

- Corruption, bad decisions and fatal mistakes

V. A Better Way for Global Public Health

- Decentralization of control and the rights of the individual

- The right to privacy: digital ID, digital certificates and private (health) data

- Free speech and the right to dissent

- International sharing and integrity of regulatory processes

- Defunding and halting gain-of-function research

- Ideational framework and approaches to global health

VI. Conclusion

3

7

- 8

- 10

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

17

- 17

- 18

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

25

- 25

- 26

- 28

33

- 33

- 35

- 36

- 39

- 40

- 40

41

World Council for Health

2

I. Introduction

Negotiations are taking place to significantly expand the control of the World Health Organization (WHO) over global public health responses and thinking via a) amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005), and b) a pandemic treaty/accord (WHO CA+). Both instruments can be seen as complementary. While the submitted IHR amendments, if approved, would greatly enhance the powers of the WHO as well as its Director-General vis-à-vis states and non-state actors, the pandemic treaty in its current form would create a new, cost-intensive supranational bureaucracy and impose an ideological framework under which to operate in matters of global health.

The World Health Assembly has set a deadline of May 2024 for putting the proposed amendments to the IHR and the pandemic treaty to a vote. Some amendments to the IHR could already be voted upon and accepted in May 2023. Amendments to the IHR are adopted via simple majority vote by delegates in the World Health Assembly with no further national ratification procedures. States retain the right to individually opt out within a specified time (10 months). If they don’t do so, the revised version automatically applies to them. The treaty, meanwhile, necessitates a two-third majority with subsequent national ratification. However, per Article 35 of the zero draft of the treaty, the agreement can come into effect on a provisional basis before the conclusion of ratification processes.

Officially, the IHR amendments and the pandemic treaty are presented as instruments to increase international collaboration, efficient sharing of information and equity in the case of another global health crisis. De facto, they can turn into instruments to replace international collaboration with centralized dictates, to encourage the stifling of dissent and to legitimize a cartel that imposes on populations interest-driven health products that generate profits over those that work better but are less profitable.

The submitted IHR amendments, in particular, provide a legal framework for monopoly power over aspects of global public health in times of actual and potential crisis. If these amendments were to be approved, this power would be exercised by a few potent WHO primary donors that exert meaningful control over the organization. These include a handful of high-income countries like the US, China and Germany as well as private stakeholders like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and pharmaceutical corporations. All of the aforementioned state and private funders have significant conflicts of interest when it comes to global public health policies. These special interests have compromised the organization. It is noteworthy in this context that the WHO only has full control over roughly a quarter of its own budget. The rest consists of earmarked voluntary contributions by its funders.

World Council for Health

3

If agreed upon, some of the IHR amendments would enable the special interests that have compromised the organization to standardize and impose how states and even non-state actors worldwide shall respond to public health emergencies and approach a variety of global health matters in general. Some of the proposed amendments to the IHR (2005), for instance, would change the nature of temporary and standing recommendations mentioned under Articles 15 and 16 that can be issued by the WHO and its Director-General (currently a Gates associate) from non-binding advice to mandatory to implement by State Parties. If the amendments pertaining to the nature and scope of these recommendations are adopted, they would provide a framework under which potential measures to be recommended listed under Article 18 of the IHR (2005) such astreatments, vaccinations, isolation and surveillance could be mandated via the WHO.

While the WHO has no effective enforcement mechanism vis-à-vis high-income countries, the proposed IHR amendments could lead to powerful governments in alignment with or even behind WHO directives arguing that these must be complied with and enforced internally due to their legally binding nature under an instrument of international law. Powerful nation states and private stakeholders in alignment with the directives as well as the WHO itself could further use the revised IHR as a legal framework in trying to legitimize health colonialism and financially pressuring lowincome countries into compliance – severely undermining their sovereignty in the process. Some of the proposed amendments to the IHR, therefore, raise serious questions concerning sovereignty and the future of democratic governance that must

be addressed.

A variety of other submitted proposals encourage systematic global collaboration to counter dissent from positions held by governments and the WHO – which is a UN agency – thereby promoting concentrated power over information. Melissa Fleming, Deputy Secretary-General of the UN, stated the following belief at a 2022 World Economic Forum (2022: 1) meeting in Davos: “We own the science and we think that the world should know it.” The draft pandemic treaty even encourages all State Parties – which includes democratic, authoritarian and dictatorial ones – to identify profiles of what is perceived as misinformation by the WHO or State Parties and to tackle information, approaches and opinions that deviate from the official line. Additional amendments to the IHR (2005) also foresee an expanded surveillance system with (preferably digital) health certificates and locator forms to ensure mass compliance with centralized directives.

World Council for Health

4

A number of IHR amendments, if approved, in addition would hand power over the identification, production and allocation of health products to the WHO under specific circumstances, effectively turning it into a cartel. Under the revised IHR, the WHO could, for example, tell State Parties to effect an increase in the production of a certain pharmaceutical – boosting the profits of the manufacturer and/or shareholders who might have relations with the WHO – for the WHO to then distribute as it sees fit, building up a patronage system over recipients.

The draft treaty, in particular, further has negative implications for global (health) security as it supports gain-of-function research despite its exceptional biosafety hazards. The escape or release of engineered pathogens from laboratory environments is not adequately classified nor focalized as a severe threat and potential cause of pandemics even though a lab leak of a human engineered virus is most likely responsible for the COVID pandemic that has led to the death of about 6.8 million people.

The proposed IHR amendments and the pandemic treaty (WHO CA+) – if agreed upon – will inevitably be used to advance the interests of a few powerful actors at the expense of others. They represent an unprecedented attempt at legalizing the concentration of undemocratic power under false pretence that necessitates a swift, effective and robust response. The envisioned legal framework for monopoly power over aspects of global public health will not lead to better pandemic preparedness but to a repetition of some of the worst decisions taken during the COVID pandemic in the event of a future emergency. The envisioned legal framework for monopoly power over aspects of global public health is not a sign of progress but represents a backsliding in human development to the times of feudal systems, colonialism and centralized empires.

The World Council for Health (WCH) unites over 190 coalition partners globally. The WCH calls for the amendments to the IHR (2005) as outlined in Chapter II of this document as well as for the pandemic treaty as currently proposed to be rejected. They represent a framework for the illegitimate exercise of global governmental power without popular accord, constitutional control mechanisms or accountability. As such, they create a dangerous precedent if passed. The scope of the advisory WHO mandate and the powers provided to the WHO via the IHR (2005) should not be expanded.

World Council for Health

5

Failures in the responses to recent global health emergencies originate with the very actors that would be empowered further by the proposed instruments, if adopted. The failures of both nation states as well as WHO bureaucratsin responding to recent public health emergencies, and the special interests compromising both the organization as well as national health agencies, must be carefully investigated.

The World Council for Health further calls for immediate legislative measures against any attempted or existing monopolization of global or national health and related fields whether through the WHO or other means. It is well established that monopoly power eliminates free choice and competition, thereby violating individual rights while dramatically reducing quality and innovation. There are few fields where this has consequences as dire as in the area of human health.

In addition, undue concentration of power presents a threat to democratic systems and the right of people to self-governance. Democracies are preserved by preventing a build-up of concentrated power and by breaking up monopolies while at the same time safeguarding essential democratic core values. Without adequate legislative measures, consolidation of power and thereby the corruption of political processes by the few continues unabatedly with fatal consequences. Ownership of any form of governance lies with the people as well as the individuals they elect to serve them as representatives which in turn need to be subjected to efficient control mechanisms to prevent overreach. Above all, governance needs to always be grounded in the dignity of the individual and core democratic values. Global governance cannot come at the cost of democratic governance

Purpose of this document

The present document showcases – with original references – the most important IHR amendments that have been proposed as well as central parts of the pandemic treaty (WHO CA+) draft and explains why they differ from previous approaches to global public health in a significant way. It further illustrates why the undue concentration of power in the field of global public health and the provision of a legal framework for such using the WHO constitute a threat to health, sovereignty and democracy that needs to be urgently addressed. In addition, legislative and educational measures are recommended in this document to strengthen public health and to achieve better preparedness, efficient international collaboration and sharing with regards to global health emergencies while avoiding monopolization and ensuring the robustness of democratic ideals in times of crisis.

World Council for Health

6

II. International Health Regulations Amendments

The concept behind the International Health Regulations can be traced back to a series of International Sanitary Conferences first held in Paris in 1851 in the aftermath of the European cholera epidemics. These conferences focused on curbing the spread of cholera, plague and yellow fever by standardizing quarantine regulations while safeguarding international trade and travel. The conferences also provided a forum for scientific discourse. Participants eventually negotiated a number of international sanitary conventions. As per Gostin & Katz (2016: 266) the “raison d’être of the earliest treaties grew out of a perceived security imperative for powerful countries. Most important was self‐protection against external threats [i.e., the spread of so-called Asiatic diseases to Europe], rather than safeguarding the public’s health in every region of the world.” Participants were mostly European powers (including Russia and Turkey) and the United States.

When the WHO was formed in 1948, it assumed responsibility over the field of infectious diseases. The organization issued the International Sanitary Regulations in 1951, eventually revising and renaming them into the International Health Regulations in 1969. Basic obligations of State Parties according to the IHR (1969) were that they notified the WHO of certain infectious disease outbreaks, when they occurred, and ensured some public health capabilities at points of entry/exit. Cooperation of states with the WHO was based on ad-hoc diplomacy and limited to few diseases. In 1995, the World Health Assembly decided that the IHR (1969) were no longer an adequate instrument to address modern challenges when it came to infectious diseases and asked for them to be significantly revised. This proposition received more urgency during the SARS outbreak of 2003.

The revision process resulted in the International Health Regulations of 2005 that are currently binding on 196 State Parties – the 194 WHO member states plus the Holy See and Liechtenstein. According to Fidler (2005: 343), the IHR (2005) “embody a new strategy – global health security – implemented through a new approach – global health governance. […] Such integrated governance is unprecedented in international public health and represents a conceptual breakthrough in global governance of significance beyond the public health realm.”

World Council for Health

7

The IHR (2005) provided new powers to the WHO and expanded the scope of the regulations beyond just a few diseases. Countries now had to notify the WHO of any events that might constitute a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). The WHO Director-General further was given the sole power to declare PHEICs. State Parties also agreed to a number of obligations concerning the establishment of core capacities to detect, assess, report, and respond to public health emergencies of international concern. While the IHR (2005) set the stage for a form of global health governance, they did so in a limited scope and without significant challenges to the sovereign status of nation states. However, this changes with the amendments to the IHR (2005) proposed in late 2022 and currently under review.

In January 2022, the US government under President Biden made far-reaching proposals to amend the IHR (2005). While most of the suggestions failed in the World Health Assembly, mostly due to African opposition, a wider process was started which called for amendments to the IHR (2005) to be proposed by State Parties. All in all, 16 State Parties either on their own or in association with regional institutions (such as the EU, the WHO African Region, the Eurasian Economic Union and MERCOSUR) submitted proposals. The WHO tasked its International Health Regulations Review Committee (IHRRC) with an assessment of the suggested amendments. In its report published on February 6, 2023, the IHRRC explains that while some amendments constitute a reiteration of existing normative commitments, others “introduce unprecedented obligations, as well as powers for WHO to direct States and non-State actors” (WHO 2023: 57). The most significant proposals are discussed hereinafter.

A. Mandatory measures and state sovereignty

Article 15 of the International Health Regulations (2005) states: If “it has been determined […] that a public health emergency of international concern is occurring, the Director-General shall issue temporary recommendations”. Article 16 adds that the “WHO may [also] make standing recommendations of appropriate health measures […] for routine or periodic application.” In the IHR (2005), the temporary recommendations issued by the Director-General and the standing recommendations are defined as nonbinding advice to consider. [1]

A number of the newly proposed amendments, if adopted, would change the nature of the recommendations that can be issued making them mandatory and legally binding.

[1] While the International Health Regulations (2005) are a legally binding document under which State Parties agree to fulfill delineated obligations outlined in the document, they do not give power to the WHO nor its Director-General to issue obligations at will to emerging situations. Instead, the WHO and its Director-General in such situations may, per the IHR (2005), only issue non-binding recommendations.

World Council for Health

8

The amendments would achieve this by removing the descriptor non-binding from the definition of the terms temporary recommendations and standing recommendations in Article 1 while simultaneously inserting a mandate to follow these in a variety of subsequent articles. For instance, the IHRRC (2023: 55) in its report notes with regards to a proposed New Article 13A: “This proposal […] renders mandatory the temporary and standing recommendations addressed under Articles 15 and 16.” With regards to Paragraph 7 of the submitted article, the Committee continues that “these proposals effectively give WHO the authority to instruct States” (ibid.: 57). Concerning a suggested amendment to Article 42, the IHRRC (2023: 67) explains likewise: “The proposed amendment to include a reference to temporary and standing recommendations seems to make application of these recommendations obligatory”.

Different amendments would also significantly expand the powers of the DirectorGeneral. An amendment to Article 15, for example, would enable the Director-General to issue recommendations not only during a PHEIC declared by him or her but in all situations that are assessed by him or her to have the potential to become one (WHO 2023a: 15). An addition to Article 42, meanwhile, states that WHO measures such as recommendations made by the Director-General not only “shall be initiated and completed without delay by all State Parties“ but that “State Parties shall also take measures to ensure Non-State Actors operating in their respective territories comply with such measures“ (ibid: 22). The IHRRC writes that “non-State actors are not parties to the Regulations“ and that the “Committee is concerned that the proposed amendment goes too far in implying that States Parties must oblige, through legislation or other regulatory measures, non-State actors to comply with measures under the Regulations“ (WHO 2023: 67).

Article 18 of the IHR features a non-exhaustive list of measures the WHO may tell State Parties to implement via recommendations when it comes to persons. This list includes among other things to require medical examinations, to review proof of medical examinations and laboratory analysis, to require vaccination or other prophylaxis, to review proof of vaccination or other prophylaxis, to place individuals under public health observation, to implement quarantine or other health measures and to implement isolation or treatment (cf. WHO 2023a: 17).

The proposed amendments that would make recommendations issued by the WHO or its Director-General mandatory raise serious questions regarding their ramifications for state sovereignty and democratic governance that need to be urgently addressed. Answers might differ from nation to nation, some being more vulnerable than others.

World Council for Health

9

B. Surveillance: (digital) health certificates and locator forms

In order to ensure and monitor mass compliance with centralized directives and mandates, a number of State Parties – most notably the European Union that is headed by the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (a recipient of the Gates Foundation Goalkeepers Award, whose husband works for a biotech company involved in the production of Pfizer’s mRNA COVID products) – have introduced amendments to establish a control system, by preference digital, based on health certificates and locator forms. The proposals include vaccine certificates, prophylaxis certificates, laboratory test certificates, recovery certificates and passenger locator forms.

The IHRRC notes that some “States Parties have proposed targeted amendments to include, inter alia, digital certificates or certificates with a quick response (QR) code” and that while digital certificates or forms might not be technically feasible in every corner of the world “digitalization should be used wherever possible” (WHO 2023: 21). A number of amendments propose to use websites and/or QR codes as means for control and surveillance. Some aim at “leveraging digital technology; and introducing standard operating procedures for all points of entry” (ibid.: 82). While some of the amendments suggest that the World Health Assembly should define technical requirements for global digital health certificates (i.e., regarding verification means, interoperability etc.), the IHRRC submits for consideration “whether the Health Assembly is the most appropriate body” to solve this task “or whether this responsibility should be entrusted to the Director-General [Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus]” (ibid.: 62).

Amendments concerning the use of (digital) health certificates or locator forms for control and surveillance have not only been proposed with regards to articles relating to international health emergencies but also in relation to Article 23 which is about general health measures on arrival as well as departure. According to the IHRRC, this article applies to all situations, not just public health emergencies of international concern (PHEICs). Submitted amendments to Article 23, for instance, include a “new proposed paragraph 6 [that] introduces a specific reference to passenger locator forms as part of the documents that may be required, and a preference for these to be in digital format” (ibid.: 61). Another amendment suggests to include information concerning laboratory tests in travellers’ health documents. The IHRRC manages to note: “[G]iven that Article 23 applies to all situations, not only PHEICs, the Committee is concerned that such a requirement may overburden travellers, and may even raise ethical and discrimination-related concerns.” (ibid.: 62) In general, the IHRRC also acknowledges a concern regarding “the appropriate level of protection of personal data” (ibid.: 66).

World Council for Health

10

As explained by the Indonesian health minister Sadikin during the G20 Summit in Bali in November 2022, the introduction of global digital health certificates constitutes a main aim in the revision of the IHR (2005). Indonesia itself has already started implementing mandatory digital health certificates by using an app that can be downloaded via Android and Apple. The country provides an example of how global digital health certificates, if adopted via the IHR amendments, can be abused by those in power to coerce people, including children, into receiving medical treatments, to restrict their movement, to compel the personal use of certain digital apps and to thereby mine private (health) data.

As of January 2023, for (re)entry into the country, Indonesia imposes on its own nationals aged 18 and above – against scientific evidence and basic ethics – the obligation to provide proof of having received three doses of COVID-19 vaccination and of having the so-called Peduli Lindungi (citizen health app) installed with personal data and vaccination status (cf. Indonesian Embassy 2023). For passengers on domestic flights, trains and ferries, children aged 6–17 are required to provide proof of one dose of COVID-19 vaccination (although contraindicated and potentially harmful), those aged 12 and over must show such proof via the Peduli Lindungi citizen health app (cf. UK.GOV 2023).

“So, let’s have a digital health certificate acknowledged by WHO. If you have been vaccinated or tested properly, then you can move around. […] Indonesia has achieved, G20 countries have agreed to have this digital certificate using WHO standards and we will submit it into the next World Health Assembly in Geneva as a revision to [the] International Health Regulations.”

– Indonesian Health Minister

Sadikin (November 2022)

Digital health certificates are a tool for the empowerment of the few and the submission of the masses. Digital health more generally is also becoming an industry with private patient data turning into a product in the surveillance economy. The Indonesian government, for instance, is in the process of digitalizing its whole health system for which it receives support from and is coordinating with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation among others. Changes include the wide, partly mandated use of a citizen health app and applications that contain digital medical records of individuals.

World Council for Health

11

C. Countering dissent globally

Besides control over measures and over mass compliance, the proposed amendments to the IHR (2005) also aim for control over information. Introduced amendments call for “countering the dissemination of false and unreliable information” (WHO 2023a: 25, 26) and for the WHO to strengthen its capacities on a global scale to “counter misinformation and disinformation” (ibid.: 40). The IHRRC even suggests that the WHO might have an obligation “to verify information coming from other sources than States Parties” (WHO 2023: 21).

The IHRRC explains that “[m]isinformation and disinformation can […] impede public confidence in, and compliance with, governmental or WHO guidance” (WHO 2023: 21). It further states that core human rights such as freedom of speech and freedom of the press need to be balanced with what the WHO and governments proclaim to be accurate information at any given moment (cf. ibid.: 21). This narrative is dangerous, anti-democratic and the precise inverse of what should happen based on the lessons

learned from COVID.

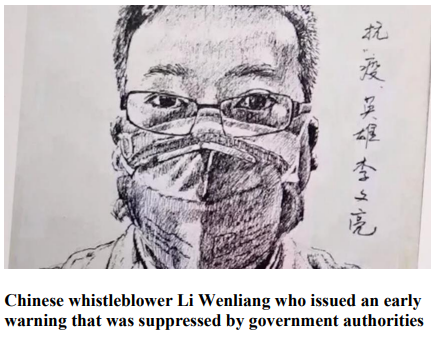

The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak could have been contained early on and the vast majority of what followed could have been prevented. This did not happen explicitly because of false and fatal governmental as well as WHO guidance in the early months of the coronavirus outbreak (which probably started in Wuhan in September 2019). This also explicitly did not happen because Chinese government authorities stifled free speech, censoring any attempts of frontline hospital physicians in Wuhan to warn the world about what they saw as severe SARS-like symptoms in their patients in late 2019. Whistleblowers like Dr. Li Wenliang and his colleagues were arrested. As one op-ed in The Guardian (2020: 1) put it: “If China valued free speech, there would be no coronavirus crisis.“

World Council for Health

12

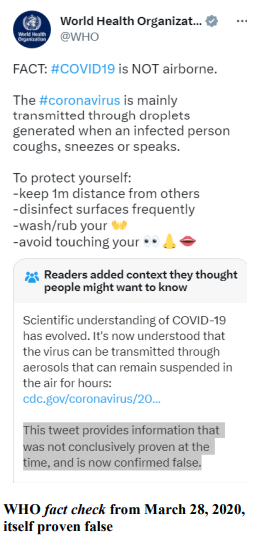

What the IHRRC also fails to mention is that while Chinese whistleblowers were fighting against government censorship to warn the world, the WHO promoted the false official line that there was no evidence of human-to-human transmission in the case of SARSCoV-2, despite clear evidence to the contrary. During the course of the pandemic, the WHO went on to support a number of false theories. The organization, for instance, maintained that COVID was not airborne and that saying otherwise was spreading misinformation, until it was forced to change its position after overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary. It also downplayed the significance of natural immunity.

Still, the IHRRC and respective amendments to the IHR (2005) seek to legitimize and enshrine as new norms dangerous appeals to authority (governmental and WHO) as well as stifling of dissent. This prepares the ground for the next potentially life-saving early warning that goes against government interests – as is often the case – to be suppressed, for dissenting voices that might turn out to be right to be censored and for those calling out mistakes by authorities to be crushed. All of these things have devastating consequences for the well-being of societies and the ability of people to stand up against government injustices. The IHRRC report as well as the proposed IHR amendments peddle the worrisome, false, authoritarian and antiquated idea that a few have a right to decide what is true and what is not, that their verdict is final and beyond doubt, even if they have been proven false a thousand times. Thereby, they seek to establish an anti-democratic monopoly over the content and flow of information.

D. Cartel rights and regulation

Some proposed amendments aim to hand power to the WHO over the global identification, production and allocation of health products in times of crisis (cf. WHO 2023a: 13–14). If adopted, the WHO would be able to identify which products “are required to respond to public health emergencies of international concern” (ibid.: 13). It could further tell states “to scale up production of [hand-picked] health products” (ibid.: 13). The submitted amendments assert that upon “request by WHO, States Parties shall ensure the manufacturers within their territory supply the requested quantity of the health products to WHO or other States Parties as directed by WHO in a timely manner in order to ensure effective implementation of the allocation plan” (ibid.: 13). The IHRRC notes that it “is not readily apparent whether States could be in a position to do so, without altering their domestic regulation of private actors operating in their territory” (WHO 2023: 57).

World Council for Health

13

One suggested amendment sees a role for the WHO in also creating standardized “regulatory guidelines for the rapid approval of health products of quality” (ibid.: 14). Concerning the latter suggestion, the IHRRC is hesitant as it “may be inadvisable from a legal perspective to require that WHO develops such regulatory guidelines, as the liability in the event of a significant safety flaw that appears postmarketing of the product will then fall chiefly on the Organization” (WHO 2023: 54).

The infrastructure required to implement the amendments related to the WHO allocation mechanism would be established via the complementary pandemic treaty. The latter would set up the WHO Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network (aka The Network), if adopted. The Network is discussed in the section Pandemic Treaty (WHO CA+) of this document.

A central aspect of the proposed amendments that relate to the allocation mechanism is the idea that any health measures undertaken by State Parties themselves in general shall not cause impediment to the WHO’s mechanism (see amendments to Article 43). In that case, the respective State Party shall provide reasons to the WHO. The latter may then ask the State Party to modify or rescind the measures. If the State Party has an objection, the matter is referred to the WHO’s Emergency Committee whose decision shall be final. The State Party shall then report on the implementation of said decision. (WHO 2023a: 23–24)

E. Unsolicited offers and obligation to cooperate

Some of the proposed amendments to the IHR, if adopted, favor making unsolicited offers towards potential recipients of assistance and introduce an obligation to cooperate on the side of potential providers of assistance.

World Council for Health

14

An amendment to Article 13, according to the IHRRC ”introduces an obligation for [a] State Party to accept or reject [an] offer of assistance from WHO within 48 hours, and if the offer is rejected, the obligation for the State Party to provide to WHO the rationale for rejection.” The IHRRC acknowledges: “The obligation for States Parties to accept or justify rejecting WHO’s offer of assistance may undermine the sovereignty of the State Party concerned and risks undermining the purpose and spirit of genuine collaboration and assistance. It is the prerogative of States Parties to request or accept assistance, not to be the recipient of unsolicited offers, accompanied by an obligation to justify the refusal and an unrealistic time frame in which to respond. Furthermore, the proposal that WHO share the rationale for rejection, while intended to promote transparency, may not be conducive to an atmosphere that fosters collaboration. It could be interpreted as a default approach of mistrust to States Parties that reject offers of assistance.“ (WHO 2023: 50)

A new Annex 10 under “obligations of duty to cooperate” further states: “State Parties may request collaboration or assistance from WHO or from other State Parties […]. It shall be obligation of the WHO and State Parties, to whom such requests are addressed, to respond to such request, promptly and to provide collaboration and assistance as requested. Any inability to provide such collaboration and assistance shall be communicated to the requesting States and WHO along with reasons.” (WHO 2023a: 50) The IHRRC notes that the “obligations set out in paragraph 1 of this proposed new Annex appear to be absolute and unconditional” (WHO 2023: 89).

F. Sharing of pathogen samples and genetic sequence data

There are a number of conflicting amendments with regards to the sharing of pathogen samples and genetic sequence data (GSD) with the WHO. While one proposal states that the sharing of genetic sequence data (GSD) of pathogens shall not be required, a ”large grouping of amendments […] by several States Parties introduce the obligation of States Parties to share with WHO GSD (although different wording is used in different proposals), as well as in some cases, to also share additional data” and “one proposal […] introduces an obligation for WHO to share information received under this paragraph with all States Parties within the context of research and for risk assessment purposes“ (WHO 2023: 38). Other suggestions “introduce specific collaboration in the form of exchange of pathogen samples and GSD” (ibid.: 70).

World Council for Health

15

While the IHRRC notes that “requiring the sharing of samples and the transfer of genetic material to WHO may raise issues of the mandate, capabilities and liabilities of WHO“ (ibid:. 39), the complementary pandemic treaty, if adopted, would establish the WHO Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System (PABS System) for that exact purpose, raising biosafety and other security concerns. The PABS System is discussed further in the section Pandemic Treaty (WHO CA+) of this document.

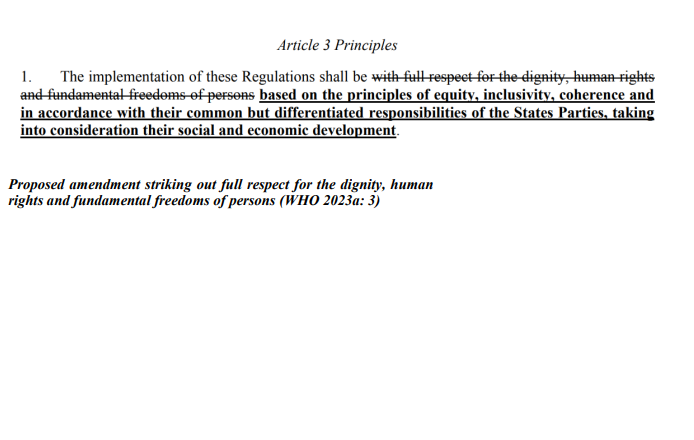

G. Discarding human rights

An amendment submitted by India is unlikely to be pursued further but presents a stark reminder that the rights of the individual as defined in the 1948 Declaration on Human Rights cannot be taken for granted. A significant number of governments worldwide do not believe in these principles. Under Article 3, India has made the proposal to strike out as guiding principles of the International Health Regulations the full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons.

World Council for Health

16

III. Pandemic Treaty/Accord (WHO CA+)

Work on a WHO pandemic treaty was proposed publicly in December 2020 by European Council President Charles Michel. The initiative was backed by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. The pandemic treaty (currently referred to as WHO CA+) is a new instrument complementary to the IHR amendments. The WHO pandemic treaty is being considered for adoption under Article 19 (which relates to the adoption of conventions or agreements) of the WHO Constitution with an additional consideration of the suitability of Article 21 (which is concerned with the adoption of regulations). A zero draft of the treaty was published in February 2023.

Based on the zero draft, the treaty, if adopted, would establish a new supranational bureaucracy. The governing body of the new bureaucracy would be the so-called Conference of the Parties (COP) which would be the sole decision-making organ with regards to matters relating to the accord. Hereinafter, some of the other main points of the proposed pandemic treaty are being discussed.

A. Recognizing the authority of the WHO and global health governance

The proposed pandemic treaty (WHO CA+), if adopted, would cede a significant and inappropriate amount of authority to the WHO. Parties to the treaty, according to the zero draft, have to recognize the central role of the WHO as “the directing and coordinating authority on global health” (WHO 2023b: 5) as well as its central role “as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work, in pandemic prevention, preparedness, response and recovery of health system, and in convening and generating scientific evidence” (ibid.: 4). Given the compromised, unelected and unaccountable nature of the WHO, no such generalized authority should be ceded to the organization.

The zero draft further commits the Parties to “contribute to research and inform policies on factors that hinder adherence to public health and social measures [such as mask-wearing or lockdowns], confidence and uptake of vaccines [such as the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA products], use of appropriate therapeutics and trust in science [WHO positions] and government institutions” (ibid.: 24). Results of such research will be used to try to increase compliance with centralized authority and directives.

World Council for Health

17

B. Tackling dissenting views globally and identification of profiles

Like some of the submitted amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005), the zero draft of the pandemic treaty under Article 17 encourages the tackling of what the WHO regards as “false, misleading, misinformation or disinformation, including through promotion of international cooperation” (WHO 2023b: 23). The proposed treaty goes beyond the suggested amendments in that it also asks for the explicit identification of “profiles of misinformation” (ibid.: 23).

Neither the draft of the pandemic treaty nor the

proposed amendments to the IHR (2005) show any recognition of the fact that the WHO and executive branches of government have themselves put out significant amounts of false and misleading information throughout the COVID pandemic and beyond. The regular use of systematic propaganda by governments before, during and after wars as well as other forms of conflict is not taken into account either. Both suggested instruments contain the viewpoint that an unaccountable, compromised supranational organization like the WHO and national governments should be allowed the role of arbitrators concerning the validity of information – with implications beyond public health.

C. WHO Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network

The pandemic treaty, if adopted, would establish the WHO Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network (the Network). While mechanisms to facilitate the just and timely global supply of medicines and other health products needed in the prevention and treatment of disease as described under Article 6 are essential, the compromised nature of the WHO as well as the lessons learned during COVID are reasons for doubt whether such mechanisms should be entrusted to the WHO or placed under any other single centralized authority.

World Council for Health

18

There is a real risk that the WHO Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network – instead of distributing those products that work best and have the highest safety profiles, which might in some cases be off-patent medicines and unpatentable agents – will be used to push selected profitable pharmaceutical products with little understood safety profiles onto a wider spectrum of the world population, especially if the complementary amendments to the IHR (2005) are adopted giving the WHO more power to do so. Public funds might end up getting systematically redistributed to selected vested interests via the WHO Network. Those public funds and distribution mechanisms might be better placed with and entrusted to diverse charitable organizations that have a proven track record of withstanding corporate interests, offer adequate response capacities on the ground and are trusted by vulnerable populations.

D. Standardization of regulation and acceleration of approval

Article 8 of the draft treaty aims at the harmonization of regulatory requirements at the international and regional level as well as at an acceleration of the approval and licensing of novel products for emergency use during a pandemic. This part of the proposed treaty corresponds with a campaign conducted by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) led by Richard Hatchett who once worked under Anthony Fauci. CEPI was founded in 2017 by the private, unaccountable World Economic Forum (WEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and others to accelerate the development of vaccines and shorten the process to a mere 100 days. In comparison, regular vaccine development takes 5 to 10 years in which safety and efficacy are assessed in clinical trials, regulatory approval processes are passed and widespread manufacturing is initiated.

While potential therapeutics should be made available in an accelerated manner to those that want to try them in life-threatening or life-altering situations (Right to Try), the lessons of the COVID pandemic show that reducing regulatory standards for the approval of novel products still in an experimental phase carries considerable and even fatal safety risks, especially when the potential of severe side effects is being censored by governments and private stakeholders financially invested in said products. An added concern relates to the fact that governments invested in little understood, fasttracked experimental mRNA COVID products approved for emergency use sought to mandate their uptake, utilizing systematic coercion and propaganda. Ensuing political pathologies directed at individuals that did not agree to be injected were pronounced. Today, world-renowned physicians and scientists are calling for the mRNA COVID products to be pulled from the market due to extensive safety concerns and lack of efficacy against transmission.

World Council for Health

19

Generally, it is advisable to enshrine an individual Right to Try with regards to novel therapeutics, while at the same time preventing the undermining of prudent regulatory requirements when it comes to wider approval.

E. Support for gain-of-function research

The draft treaty declares that when it comes to “laboratories and research facilities that carry out work to genetically alter organisms to increase their pathogenicity and transmissibility” standards should be adhered to in order “to prevent accidental release of these pathogens” but that it needs to be ensured that “these measures do not create any unnecessary administrative hurdles for research” (ibid.: 16).

The support for gain-of-function research enshrined in the proposed treaty is highly problematic as the risks associated with unethical gain-of-function research on pandemic potential pathogens (PPPs) such as SARS significantly outweigh the benefits. Kahn (2023: 1) explains how like “Icarus flying too close to the sun, some scientists working in laboratories have been pushing the fates by creating pathogens (i.e., microbes that make people sick) that are more dangerous than those occurring in nature. […] Gain-of-function research involves giving microbes such as bacteria and viruses enhanced capabilities that they might not normally possess in nature. This research currently receives almost no national or international oversight.”

SARS-CoV-2 was genetically altered at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China; it is likely, according to former CDC Director Robert Redfield, that US tax dollars paid for the gain-of-function research that created the virus. The pandemic, that in all probability resulted from a scientifically engineered SARS-CoV-2, killed about 6.8 million people worldwide, according to the WHO, and led to an incursion on core human rights. The proposed pandemic treaty reveals a worrisome disregard for the likely laboratory origins of the COVID pandemic and the exceptional devastation that can be caused due to biosafety hazards associated with gain-of-function research. The world could witness the escape or release of a significantly more deadly human engineered virus than SARSCoV-2. As an example, Kahn (2023: 1) notes:

World Council for Health

20

“With a case fatality rate of approximately 56 percent, the H5N1 avian influenza virus is much deadlier than SARS-CoV-2, which has an estimated case fatality rate below 2 percent. The H5N1 avian influenza virus first emerged in Hong Kong in 1997 from infected birds, but it was unable to spread readily from mammal-to-mammal.

Once a pathogen gains the ability to spread easily from mammal-to-mammal, the risks of it spreading to humans increases. Enter Ron Fouchier, a virologist from Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands. In 2011, he and his colleagues decided to give the H5N1 avian influenza virus the enhanced capability of airborne spread between mammals.“

F. Sharing of pathogen samples and genetic sequence data

The pandemic treaty, if adopted, would set up a WHO Pathogen Access and BenefitSharing System (PABS System) that has a business element to it and is accessible by all State Parties. Article 10 states:

“1. The need for a multilateral, fair, equitable and timely system for sharing of, on an equal footing, pathogens with pandemic potential and genomic sequences, and benefits arising therefrom, that applies and operates in both inter-pandemic and pandemic times, is hereby recognized. In pursuit thereof, it is agreed to establish the WHO Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System (the ‘PABS System’) under this WHO CA+. […]

2. The PABS System shall cover all pathogens with pandemic potential, including their genomic sequences, as well as access to benefits arising therefrom, and ensure that it operates synergistically with other relevant access and benefit-sharing instruments. […] Facilitated access shall be provided pursuant to a Standard Material Transfer Agreement, the form of which shall be set out in the PABS System and that shall contain the benefitsharing options available to entities accessing pathogens with pandemic potential […] The PABS System […] will promote effective, standardized, real-time global and regional platforms that promote findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable data available to all Parties.” (WHO 2023b: 17)

While access to genetic sequence data is, for instance, important in the rapid development of test capacities, the PABS System as currently proposed and accessible by all State Parties – dictatorships, countries engaged in war and state sponsors of terrorism included – presents a liability. The draft of the pandemic treaty does not address the significant security implications related to the sharing of pandemic potential pathogens (PPPs) and their genetic sequence data. The PABS System creates an additional biosafety risk to the one stemming from existing national and international research – with oversight becoming even less adequate than it already is. The WHO does not have the capacities to guarantee that data or material won’t end up in the wrong hands. The proposed PABS System further sends the wrong signal as it may encourage the expansion of gain-of-function research when it should be curtailed and halted. The WHO has no means to ensure that shared materials or data won’t be used in scientific experiments that create new hazards.

World Council for Health

21

G. One Health and pandemic/epidemic root cause analysis

The One Health approach – a relatively new term – is rooted in older concepts that recognize a close link between the health of humans, animals and ecosystems. Under the One Health approach, expertise in these fields is being integrated. The well-being of humans, animals and ecosystems is closely interlinked. However, a variety of organizations such as the WHO are trying to misappropriate this understanding for their own political ends.

The zero draft of the WHO treaty uses a One Health language to promote a focus on the human-animal-environment interface as an origin of infectious diseases and pandemics. It identifies as “the drivers of the emergence and re-emergence of disease at the human-animal-environment interface“ specifically “climate change, land use change, wildlife trade, desertification and antimicrobial resistance“ (WHO 2023b: 24). Article 18 commits State Parties “in the context of pandemic prevention, preparedness, response and recovery of health systems, to promote and implement a One Health approach that is […] coordinated and collaborative among all relevant actors” (WHO 2023b: 24) and to “take the One Health approach into account at national, subnational and facility levels” (ibid.: 25). State Parties also acknowledge via the treaty the importance of the so-called Quadripartite which consists of the WHO, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Organization for Animal Health and the UN Environment Program in addressing One Health-related issues.

Through its one-sided focus, the zero draft of the treaty diverts attention away from gain-of-function research as the most likely origin of the COVID pandemic. A video released by the WHO to garner support for the pandemic treaty, similarly, features Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus addressing pandemics as “a common threat that we did not fully create and cannot fully control – a threat that comes from our relationship with nature itself [these words are set to a video of two young people taking a walk in the forest]“. This is ironically followed by “it is vital that we all make an honest assessment of the [COVID] pandemic and learn its lessons, so we don’t repeat the same mistakes again. We owe it to the millions we have lost“. This narrative does not constitute an honest assessment of the COVID pandemic and its origins while also revealing a problematic, one-sided understanding of nature’s role in human health. While threats to human health can be found in nature, it also is an essential source for and driver of human health.

World Council for Health

22

Through its one-sided focus, the zero draft of the treaty fails to address a number of factors in the emergence and persistence of severe infectious diseases. Besides laboratory experiments on pandemic potential pathogens (PPPs) that subsequently leak, these can include the spread of explicitly human pathogens and the lack of provision of treatment. For instance, the single most deadly infectious disease that kills around 1.6 million people every year is human tuberculosis, caused by a primarily human pathogen that has been around for much of human history. Tuberculosis is curable in most cases, however, there is a fatal lack in the provision of adequate treatment.

The One Health approach, if applied correctly, has a central place in the prevention of a number of infectious diseases and health emergencies. However, it is prudent not to exclude important causes and sustainers of epidemics and pandemics from the equation that do not typically fall under it.

It is further noteworthy that while the zero draft of the WHO treaty focuses on One Health and the human-animal-environment interface ideologically, it appears to promote a deficient understanding of said approach. It states, for example, “that most emerging infectious diseases originate in animals, including wildlife and domesticated animals,“ (WHO 2023b: 6) while making no mention of the fact that the severity of emerging strains is a more appropriate indicator for relevance than the number, and that in many (albeit not all) instances more severe threats derive not from the animals in themselves but from the excessive, unnatural maltreatment of animals by humans.

One example is factory farming in which animals are deprived of their natural habitats and instead confined by the tens of thousands in cages in indoor facilities with poor sanitary conditions and waste management. Some experts have made the case that the A/H1N1 pandemic of 2009 might have had its origins in factory farms. (Others think it could have been created unintentionally by scientists engaged in recombinant viral research with H1N1.) BSE and its human variant, a form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD), have their origins in cows, feeding on grass along with other naturally occurring

World Council for Health

23

vegetation in nature, being given processed animal brains to eat in factory farming. With regards to the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N8 strain, the Scientific Task Force on Avian Influenza (2016: 1) concludes that typically outbreaks of this dangerous type “are associated with intensive poultry production [factory farms] and associated trade and marketing systems with spread of HPAI via contaminated poultry, poultry products and inanimate objects“. Wild birds, in contrast, are “a reservoir for [only] low pathogenic virus strains, with low prevalence“ (ibid.: 3). Marius Gilbert, an epidemiologist at the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium, explains: “Most viruses which circulate in wild birds are of low danger and cause only mild effects.“ However, when a virus finds its way into factory farms, it goes “through evolutionary change, mostly linked to the conditions in which the animals are farmed. We have seen lowpathogen viruses gain pathogenicity in farms.” (Vidal 2021: 1) Humans have turned what in nature is mostly a mild virus for the affected animals with a low prevalence in wild birds and with little ability to spread between mammals into highly virulent, lethal forms via industrialized animal farming while at the same time creating airborne forms highly transmissible from mammal to mammal via animal experimentation in gain-offunction research. As a result, Avian Influenza now has a potential of becoming a pandemic worse than COVID-19.

Factory farming is also a significant driver of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as the vast majority of produced antibiotics (about 75% globally) are used in factory farms on animals trapped in unnatural and unsanitary living conditions where pathogens develop resistance. Antimicrobial resistance is estimated to have killed 1.27 million people in 2019 alone (cf. RKI 2022: 2).

All in all, the draft treaty does not give attention to central potential causes for the emergence (such as lab leaks from gain-of-function research) and persistence (such as a lack of provision of treatment in human tuberculosis) of deadly infectious diseases not primarily related to the human-animal-environment interface while leaving aside essential tenets of a One Health approach.

World Council for Health

24

IV. Rejecting Monopoly Power over Global Health

A. The threat posed by monopolies

Democracy is preserved by safeguarding core democratic values, including in times of crisis, while preventing concentrated power in the hands of a few, and breaking up monopolies. US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis warned a century ago that we can either have concentrated wealth (and thus power) in the hands of few or democracy but that we cannot have both. US President Franklin Roosevelt similarly stated: “The first truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself.”

Anti-monopoly systems not only protect democracies but also enable free choice among competing ideas, require independent thinking, lead to the creation of free organizations, local ownership, innovation and quality in services. Without concentrated power, it becomes more difficult to corrupt political processes, compromise science, control information, suppress competition and eliminate choice. Independent actors and organizations not beholden to a centralized power structure have further proven essential in challenging and countering injustices stemming from abuse of power which is pervasive in human history.

In the field of global health, monopoly power, which by nature curtails choice, suffocates competing solutions, corrupts science, compromises political processes, seeks to control the flow of information and to stifle dissent, can be especially harmful as the area touches on the most fundamental needs of human beings. That is the reason why international collaboration and sharing to benefit global health cannot be improved by assigning concentrated power to an unelected, unaccountable and compromised supranational organization like the WHO. Different forms of solutions must be sought and developed to address challenges related to global health.

World Council for Health

25

B. Who runs the WHO – structural reality

The once noble idea of a global health organization working for mankind’s best interests has been replaced by an entity largely driven by the financial and ideological interests of overreaching private stakeholders and a handful of powerful states.

The World Health Organization is steering a course that balances the interests of a few powerful countries such as the United States and Germany (two top donors), major private contributors(primarily the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Gates-funded GAVI Alliance) and China. In the 2020 to 2021 period, Germany and the European Commission led donations with US$ 1,732 million, followed by Gates-dominated enterprises with US$ 1,183 million, and the United States with US$ 693 million (cf. WHO 2023c). China is the 11th largest donor with a contribution of US$ 168 million but holds significant geopolitical influence, incl. in the World Health Assembly.

The WHO distinguishes between assessed contributions (AC) and voluntary contributions (VC). Assessed contributions derive from a percentage of the gross domestic product of each member state and cover less than 20% of the total WHO budget. Voluntary contributions (VC) come from member states, private foundations and industry. They account for over 80% of the budget. Nearly 90% of the voluntary contributions are earmarked to specific programs and locations. (cf. WHO 2023d) In the past, 80% of the total WHO budget came from assessed contributions with the WHO deciding on how to spend them while only 20% were earmarked voluntary contributions (cf. Mischke & Pinzler 2017).

World Council for Health

26

Since funds now come with caveats, the organization is compromised on a number of issues that involve the interests of its donors. The private sector and also most state actors that are tied to respective corporations (e.g., German corporations include Bayer which bought Monsanto, BioNTech or Boehringer Ingelheim; US companies include Pfizer, Moderna, Merck or Johnson & Johnson) are unlikely to get involved unless potential profits – financial or other – are involved. Margret Chan, the previous Director-General of the WHO, said in 2015: “I have to take my hat and go around the world to beg for money and when they give us the money [it is] highly linked to their preferences, what they like. It may not be the priority of the WHO, so if we do not solve this, we are not going to be as great as we were.” (Franck 2018)

A number of leading global health and antitrust experts as well as international organizations have long called for a comprehensive reform of the WHO. They have been especially critical with regards to the significant influence yielded over the organization by private corporate interests and the Gates conglomerate.

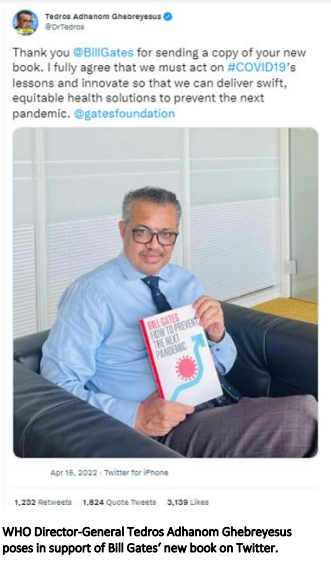

After Gates was faced with charges of unlawful monopolization against his corporation in United States v. Microsoft Corporation, his efforts moved to concentrating power in other fields, notably global public health and agriculture. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is the second largest donor to the WHO while Gates also founded and cofunds The Vaccine Alliance (GAVI) and CEPI. As contributions by the Gates conglomerate are earmarked for specific projects, the WHO doesn’t decide how the respective money is spent, Gates does. Consequently, he pays the WHO to use their infrastructure, staff and international standing for his purposes, turning it into a contract organization. James Love (Knowledge Ecology International) – who was involved in bringing the antitrust case against Microsoft in the United States, previously worked with Doctors Without Borders and played a critical role in the battle to make antiretroviral treatment accessible in Africa – states that Gates staffers come with an explicit agenda and believes that people generally do not understand what the influence that is yielded by the Gates Foundation means in practice. Bill Jeffery (Centre for Health, Science and Law) elaborates that, with regards to the Gates Foundation, the WHO is accepting funding from an organization whose financial well-being depends on the success of the processed food and pharmaceutical drug industry. At the same time, a number of leading Gates Foundation employees have previously worked for Monsanto (now Bayer) which produces glyphosate and seeks global monopoly power over seeds by genetically modifying them. Accordingly, the Gates Foundation has an interest in the WHO promoting certain pharmaceutical as well as chemical products and preventing rigid regulation of these.

World Council for Health

27

Thomas Gebauer (medico international) criticizes the excessive amount of discretionary competence handed to a single, unelected, unaccountable person over a global body: “This is a manifestation of feudal structures. We must face as democratic societies which kind of processes we have permitted to unfold by now.” (Mischke & Pinzler 2017)

Gates’ enterprises, while the most pervasive, are not the only private entities compromising the WHO. A number of private foundations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation, are also invested in the WHO, albeit to a lesser degree. Pharmaceutical corporations themselves are donating millions of US dollars to the supranational body in close chronological proximity to decisions taken by the WHO that might affect them. The WHO cherishes its long-term relationships with the industry and describes it as a partner. Even top state contributors, most of whom earmark their voluntary contributions, are tied to certain corporations which leaves them with significant conflicts of interest.

KM Gopakumar (Third World Network) further notesthat special interests not only yield influence over the WHO via donations but also place personnel inside the organization to run certain programs, thereby steering it via two fronts (cf. ibid.).

Handing more power over global health and the authority to direct State Parties as well as non-state actors operating in their territory to the WHO via the proposed amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005), inevitably lends excessive and undemocratic powers to the unaccountable special interests that have compromised the organization. Special interests would no longer need to attempt to corrupt political processes in secret backdoor deals but would have the full force of international law behind them. This prospect presents a severe threat to hard-fought for democratic systems, the sovereignty of low-income states, and global health itself.

C. Corruption, bad decisions and fatal mistakes

The work of the WHO concerning health is often subordinated to political constraints and the pervasive influence of the special interests that have compromised the organization. At the same time, the supranational bureaucracy based in Geneva suffers from a lack of effective independent oversight, accountability and humility. As a result, the WHO has been involved in excessive corruption and repeatedly made mistakes, implementing policies with severe consequences for global health, without any accountability. This is another reason why its authority should not be expanded; much less and under no pretext should the organization – or any other entity – be given monopoly power over aspects of global health, which would considerably exceed its original mandate. Examples of undue influence on WHO decision-making and fatal failures by the organization are outlined below.

World Council for Health

28

In June 2009, Margaret Chan, then the DirectorGeneral of the WHO, officially declared the influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. Cohen & Carter (2010: 1) write: “It was the culmination of 10 years of pandemic preparedness planning for WHO—years of committee meetings with experts flown in from around the world and reams of draft documents offering guidance to governments.“ In the end, the WHO let industrysponsored scientists guide its influenza policy. States that followed WHO recommendations acquired vast quantities of pharmaceutical products with tax payer money from corporations for whom the WHO scientists had previously worked. Cohen & Carter (2010: 1) continue: “But one year on, governments that took advice from WHO are unwinding their vaccine contracts, and billions of dollars’ worth of stockpiled oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza)—bought from health budgets already under tight constraints—lie unused in warehouses around the world. A joint investigation by the BMJ and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has uncovered evidence that raises troubling questions about how WHO managed conflicts of interest among the scientists who advised its pandemic planning.“

“Key scientists advising the World Health Organization on planning for an influenza pandemic had done paid work for pharmaceutical firms that stood to gain from the guidance they were preparing. These conflicts of interest have never been publicly disclosed by WHO, and WHO has dismissed inquiries into its handling of

the A/H1N1 pandemic as ‘conspiracy theories‘.”

Cohen & Carter (2010: 1)

British Medical Journal

WHO recommendations, in countries that present highly lucrative markets, served to generate billions in profits for pharmaceutical corporations with ties to the very scientists working on the WHO advice. In addition, one of the recommended medications is considered by experts to be ineffective in the treatment of A/H1N1 influenza. Back in 2009, WHO recommendations were non-binding. Lessons from the 2009 influenza pandemic provide compelling reasons why it should stay this way.

World Council for Health

29

During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the WHO not only failed to react in an adequate and timely manner, but also denounced international organizations such as Doctors Without Borders that did. The WHO stated that the outbreak would not lead to an epidemic which, nevertheless, it did. Over months, Doctors Without Borders organized and carried out emergency relief operations with sometimes up to 2,400 staff being deployed. Over 11,300 people died during this Ebola epidemic. Only after a PHEIC was declared in August 2014, the international community sprang into action to effectively stop the disease. Had the WHO and the international community reacted in a timely manner, many more lives could have been saved. (cf. Mischke & Pinzler 2017) Gostin & Katz (2016: 274) write: “The delay only looked worse with time, as leaked WHO documents revealed that the WHO’s decisions were highly political and lacked transparency.“

“After we had said as an organization in June [2014] that Ebola was out of control, it took until August for the WHO to come to the same conclusion. Especially in the beginning, the WHO made accusations against us as an organization, saying we were engaging in scaremongering and that we were sounding the alarm on something that was not as dramatic.”

Dr. Tankred Stöbe

Doctors Without Borders

(Mischke & Pinzler 2017)

Tankred Stöbe (Doctors Without Borders) elaborates that Ebola belongs to the socalled neglected diseases which have been known for a long time but don’t garner the necessary scientific attention as they mostly affect poor people in lowincome countries far away from markets that are lucrative to industry. Accordingly, the funds for the WHO section responsible for Ebola had been cut in half before the 2014 outbreak. (cf. Mischke & Pinzler 2017)

With regards to the COVID-19 pandemic, an Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR) created by the WHO found that “poor strategic choices“ were made by both governments as well as the WHO that contributed to “a toxic cocktail which allowed the pandemic to turn into a catastrophic human crisis.“ (Kupferschmidt 2021: 1) The panel sees the solution in even more centralization and in handing more power to the WHO. Instead, national governments and the WHO need to be held accountable; decision-making needs to be diversified.

World Council for Health

30

Both governments as well as the WHO made poor choices from the beginning. Early warnings by Chinese frontline clinicians from Wuhan about unusual and severe SARS-like disease symptoms in their patients were systematically suppressed by the Chinese government. The suppression of information relating to the spread of SARS-CoV-2 from November 2019 into late January 2020 – when the virus could have still been contained – is one of the worst cover-ups in history which had fatal consequences for millions of people. The WHO widely disseminated disinformation by the Chinese government via social media that there was no evidence of human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV2, although leading WHO scientists knew better and had stated so. Despite the tragic cover-up, senior WHO official Bruce Aylward would later proclaim that the “world owes China a great debt” when the country eventually started authoritarian containment measures.

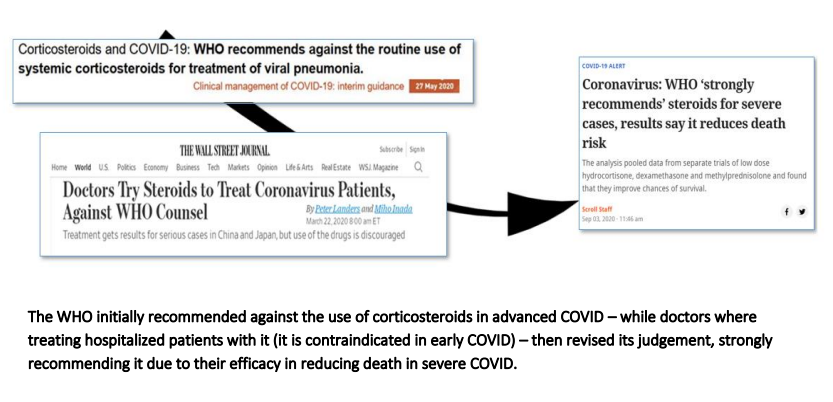

It was not until January 20, 2020, that the Chinese government finally admitted officially that human-to-human transmissions were taking place. The WHO took until January 30 to declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). During the ensuing pandemic, the WHO promoted a number of false theories (e.g., no human-tohuman transmission, COVID not being airborne etc.), downplayed essential natural immunity, published contradictory statements (one time warning against lifting lockdowns too early, then lauding Sweden’s lockdown-ignoring approach the next month) and lagged behind independent and innovative frontline physicians (for instance, when it came to the use of corticosteroids in a hospital setting).

World Council for Health

31

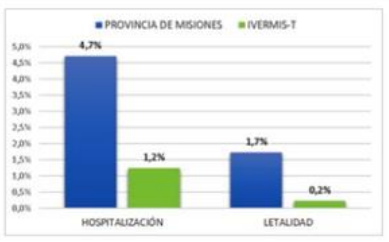

Eventually, a number of renowned frontline physicians – from different parts of the world – reported successes in the therapy of COVID when treated early. These physicians, making use of their independent clinical judgement, were ahead of both the WHO and national health agencies. Respected frontline doctors developed and published safe and effective early treatment protocols (which mainly contained repurposed off-patent medicines), hardly losing any patients to the disease when therapy was initiated early. Some local governments, from Misiones in Argentina to Mexico City and India’s Uttar Pradesh region, successfully employed versions of these early treatment protocols independently, achieving significant reductions in mortality and hospitalization as a consequence.

One of the greatest crimes of the COVID pandemic was the withholding and suppression of these early treatment protocols by both national health agencies as well as the WHO due to a singular interest in and focus on the implementation of a worldwide vaccination campaign. Had there been a recognized early treatment for COVID, the novel and profitable mRNA products, which both a number of powerful governments as well as private WHO funders such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation were significantly invested in with millions of US dollars, could not have received an emergency use authorization.

Some experts estimate that 70–80% of the global COVID deaths could have been avoided with systematic timely treatment. The suppression of safe and effective but unprofitable early treatment protocols for COVID by federal government agencies, corporate interests as well as organizations like the WHO resulted in unprecedented suffering and loss of life. It may constitute a crime against humanity.

No monopoly power should be handed to any person, institution or organization. If an entity had such powers and made poor choices or fatal mistakes, it would be difficult to counteract them and societies could crash. That is one reason why it is important to have diverse poles of power and effective democratic control mechanisms in place.

World Council for Health

32

V. A Better Way for Global Public Health

This chapter advises on essential actions required by national as well as international leaders and organizations. The proposed legislative and educational measures, among other things, build on the lessons learned during the different development phases of the COVID pandemic. Phase 1 relates to the origin of SARS-CoV-2 –which lies most likely in gain-of-function research. Phase 2 is concerned with the time period in which the spread of the pandemic could still have been prevented with the help of whistleblowers and adequate early response measures. Phase 3 is about the period that saw the main impact in mortality, which could have been significantly lessenedwith readily available safe and effective early treatment. Phase 4 relates to the recovery period which requires an honest assessment and accountability measures.

A. Decentralization of control and the rights of the individual

Based on the lessons learned from the COVID pandemic and in order to improve preparedness as well as responses to future international health emergencies, a more decentralized approach to global as well as national health than currently practiced is essential. Credence and leadership should be build on competence and working solutions rather than uncritial – as well as dangerous – appeals to authority.

While federal governments and their health agencies, as well as supranational organizations such as the WHO and self-empowered private stakeholders, failed on many levels during the COVID pandemic with fatal consequences, some local state governments and frontline physicians as well as faith-based initiatives have proven their worth. A number of local governments successfully distributed safe and effective early treatment kits. Some exceptional frontline physicians provided early warning and working treatment protocols while under significant pressure to conform with the official line. Some local initiatives, like that of a Christian priest in Peru, organized desperately needed equipment (e.g., oxygen) for communities. The aforementioned actors have their strong ethics as well as a close contact to what is happening on the ground and to affected people in common. They did not relinquish their personal responsibility to a centralized authority, thereby making a positive difference in the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

World Council for Health

33

The following actions should be taken nationally and internationally:

- The amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005) as proposed and the pandemic treaty/accord (WHO CA+) as outlined in its zero draft must be opposed and rejected when they are put to a vote. Should they pass, countries need to opt out of the revised Regulations within 10 months and need to reject ratification of the treaty.

- Legislation that limits supranational organizations to providing a forum for exchange, advice and response capabilites should be introduced, passed and implemented. These organizations have no popular mandate, are not subject to democratic control mechanisms, and lack accountability to impose rules or policies. Supranational bodies like the WHO should also generate the majority of their funds from member states. These member states should not earmark their contributions to enable the organization to act free from national interests. To further prevent corruption, it should also be prohibited for the supranational body to accept funds from private stakeholders and corporations that have financial interests in relation to the issues the organization engages with.

- Control over health policies should be decentralized via legislative measures, with local states, state parliaments, courts and referenda playing a more central role than federal governments. Legislation should also prevent any decision-making power that can override national democratic institutions being handed to an unelected supranational body.